A popular buzzword or phrase in various industries recently is the term “at scale” — which refers to building systems or services that can be delivered and sustained over a broad area for many people.

It’s actually a very pragmatic and important concept. Very often people think of amazing products and solutions. Fusion energy systems have been developed and tested to work, but we’re not able to build models to power the entire country. Quantum computers exist that can perform tasks that might take ordinary computers millions of years to accomplish. However, those computers are limited in the types of tasks they can perform, they are very expensive, and very large. They need extreme cooling systems.

There are many examples of great inventions and ideas that haven’t been brought to market with broad distribution due to various limitations.

Electric vehicles are a good example of this. We know they work. Millions of people are using them. But are electric vehicles feasible as a solution to replace those currently powered by gasoline and diesel? We would need millions of charging stations, a massive upgrade to the national power grid, a big increase in electricity production capabilities, and a nation-wide workforce of auto mechanics trained on EVs would be needed. If any of these pieces are missing, it won’t work at scale. Yesterday the CEO of Ford announced that there isn’t enough time to train all the mechanics needed for a timely switch to EVs. [Source] For more on this topic, read, “Are Electric Cars the Answer?” by Nicholas Johnson.

To do anything at scale, often requires doing everything at scale. Logistics. Manufacturing. Sales. Customer service. Technical support. The list goes on.

I’m often asked why I don’t hire employees and build a large IT services company.

The reason is simple. Many years ago, I watched a friend do just that. He built up a an ITservices business. His role became managerial, administrative, and supervisory. One day he told me, “Greg, I’ve lost my tech skills. I’m spending all my time running the business rather than working on computers.”

In addition to losing his tech skills, he was losing touch with his customers. Service delivery was becoming impersonal. The necessity of efficiency and profits demanded fast bare minimum service delivery.

When a customer calls me, we have a conversation and talk about general life events, and when the conversation gets to the point of talking about resetting their router, I say, “Okay, your router is under the desk on the right. The cords are short so you might not be able to pull it out all the way, but on the back you’ll find at the top is the power button. Your old router had the power button in the front, but this one has it in the back.”

I’m able to solve common problems in minutes over the phone, rather than needing to go on-site and charge for an in-home visit. That’s only possible because we’ve developed a relationship over 5, 10, 20, or 30 years.

Instead of hiring employees, I train other people to do what I do — provide tech services and develop long-term relationships with people. I keep doing this over and over. I’m bulling small-scale at-scale. In this way, hundreds or thousands of people can get support, all from someone they know.

This idea of building optimal small-scale service models, and duplicating them, can result in the best of all possible options.

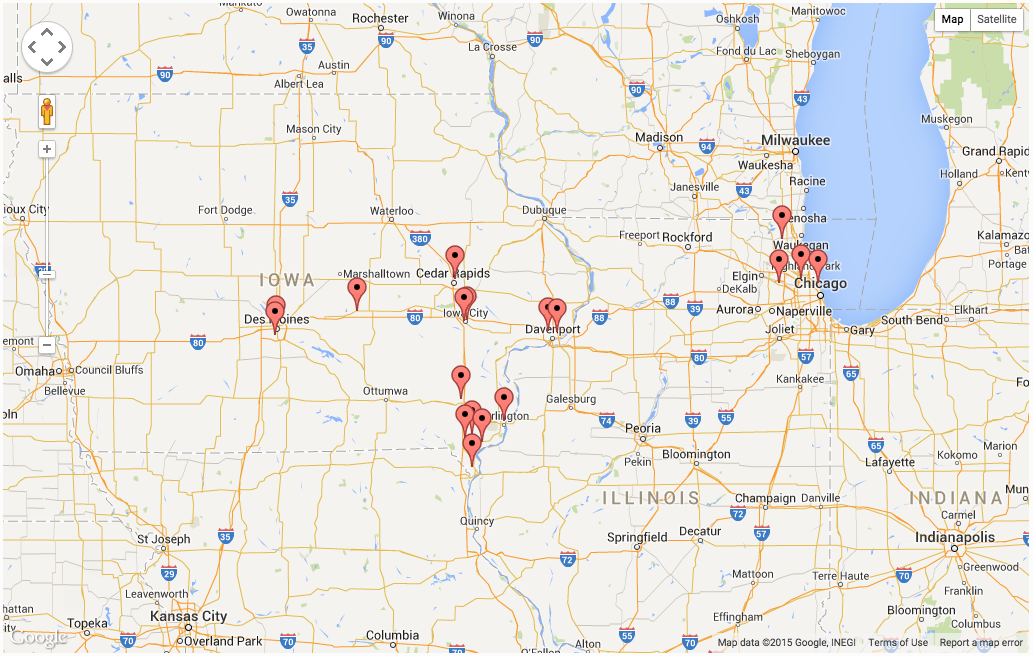

I’ve written the above as an update and addendum to my 2015 article, “Centralized and Distributed Support Models in Service Industries.” [View]

Note: Beyond tech services, the small scale at scale approach could be used for neighborhood volunteer helpers to assist those in need.